×

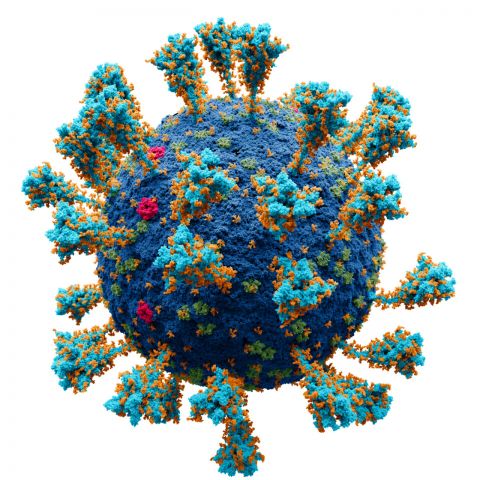

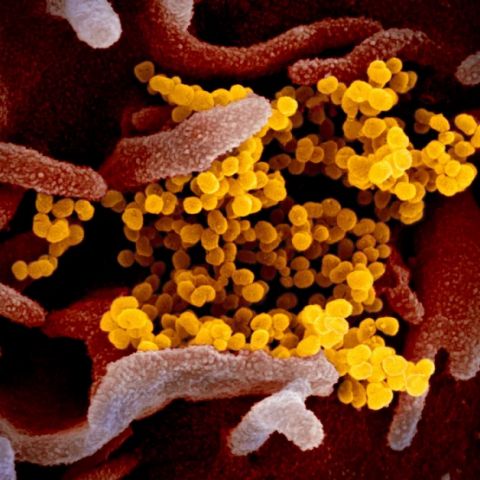

Ask anybody what the main symptoms of COVID-19 are, and they’re likely to say the same thing: a cough, fever, and a loss or change of your sense of smell and taste. However, a significant number of people – over one in thirteen of those who recover from the virus – are left with the infamous “brain fog”.

“[Cognitive symptoms] manifest as problems remembering recent events, coming up with names or words, staying focused, and issues with holding onto and manipulating information, as well as slowed processing speed,” explained Joanna Hellmuth in a statement. She’s the senior author of a new paper on the phenomenon, published this week in the journal Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology – and she thinks the answer might be in our spines.

Ask anybody what the main symptoms of COVID-19 are, and they’re likely to say the same thing: a cough, fever, and a loss or change of your sense of smell and taste. However, a significant number of people – over one in thirteen of those who recover from the virus – are left with the infamous “brain fog”.

“[Cognitive symptoms] manifest as problems remembering recent events, coming up with names or words, staying focused, and issues with holding onto and manipulating information, as well as slowed processing speed,” explained Joanna Hellmuth in a statement. She’s the senior author of a new paper on the phenomenon, published this week in the journal Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology – and she thinks the answer might be in our spines.

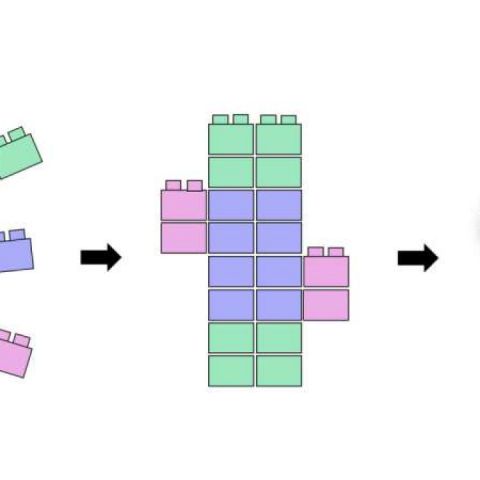

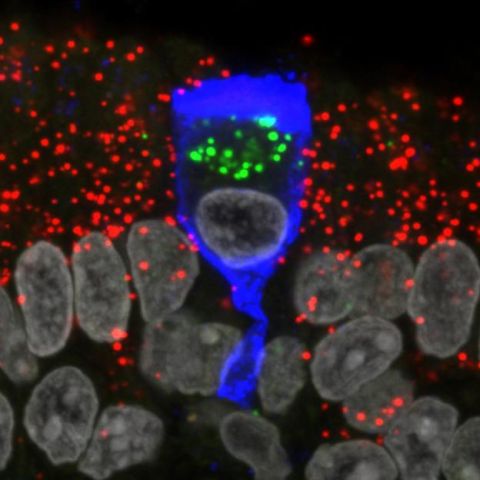

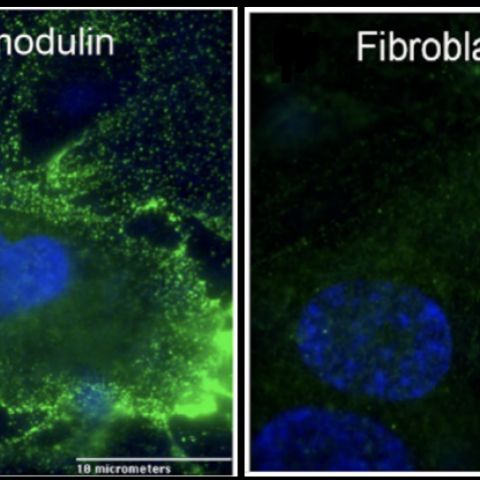

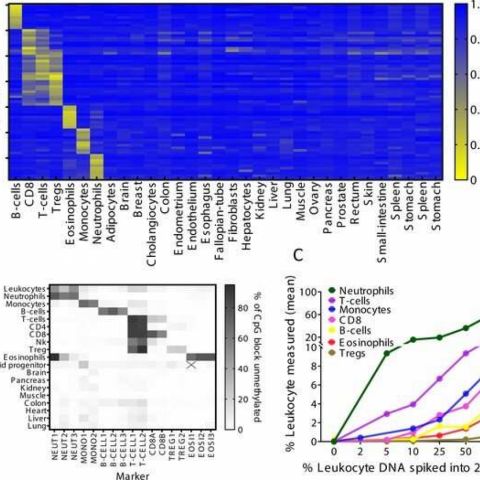

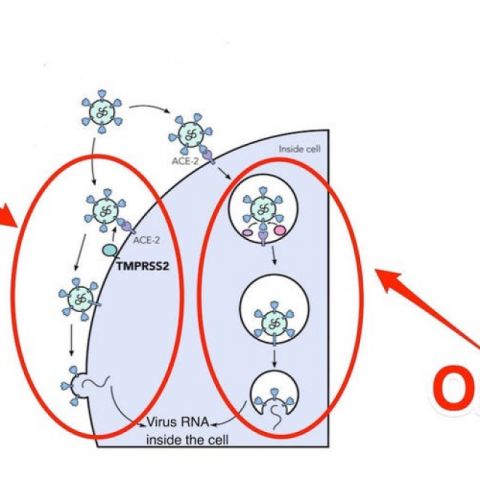

The team behind the new paper noticed something intriguing after analyzing the cerebrospinal fluid of adults experiencing cognitive symptoms after recovering from COVID-19 and comparing them to a small control group with no such after-effects. Of the 13 patients, 10 (or 77 percent) had anomalies in their fluid samples: elevated levels of protein in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid, plus the unexpected presence of certain antibodies that would usually signal an ongoing immune response.

In contrast, none of the control samples had these anomalies – and the team believes this points to a possible explanation for the sometimes debilitating cognitive effects.

Elevated proteins and antibodies in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid points to systemic inflammatory responses or brain inflammation, and “it's possible that the immune system, stimulated by the virus, may be functioning in an unintended pathological way,” said Hellmuth.

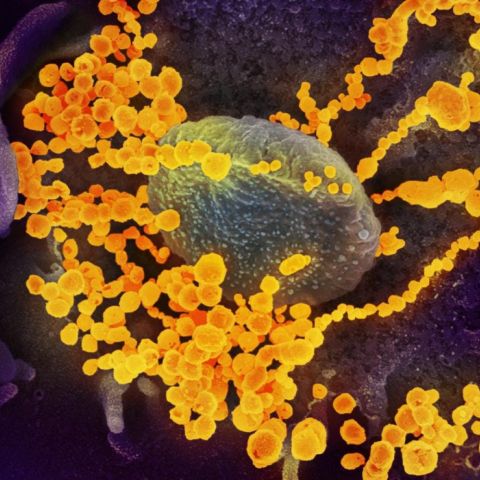

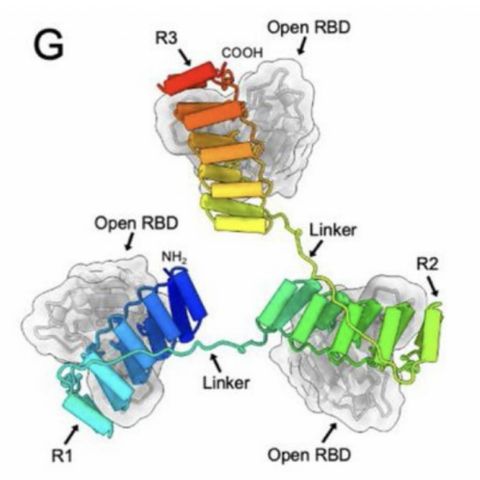

While these “turncoat” antibodies, or autoantibodies, have previously been found in people who have recovered from severe COVID-19, participants in the new study had all had relatively mild infections. None required hospitalization, and all experienced their first symptom an average of just over 10 months before the study took place – but nevertheless, Hellmuth said, this autoimmune error was seen “even though the individuals did not have the virus in their bodies.”

What’s more, there seem to be a few key risk factors for developing this “brain fog” highlighted in this study: these include diabetes and hypertension – both of which can increase the risk of stroke – plus mild cognitive impairment and vascular dementia. Also making the list was ADHD, anxiety, depression, and histories of heavy alcohol or repeated stimulant use – all associated with problems in executive function.

Although the study was limited by its small and very specific sample – only 17 participants consented to lumbar punctures, and the average age of those with cognitive impairments was 48 years old – it nevertheless does provide a springboard for further research, the paper says.

For future research, Hellmuth has a recommendation: don’t place too much importance on previously standard cognitive tests. While study participants underwent a barrage of neuropsychological assessments against criteria equivalent to those used for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, these “may not identify true changes,” Hellmuth pointed out.

“Particularly in those with a high pre-COVID baseline, who may have experienced a notable drop but still fall within normal limits,” Hellmuth added.

“If people tell us they have new thinking and memory issues, I think we should believe them rather than require that they meet certain severity criteria.”